A few stories. It's all about art.

One

I've kind of had it with pro sports. I haven't really been a sports nut anyway since I was about fourteen. But I do like sports. I especially like baseball. And once upon a time baseball really was a pastoral sport. For the spectator, at the game, the action was compact with spaces in between, and long breaks between innings. It's a game you give your attention to in little bits, and between pitches and innings you can comment to your companions, gaze over the crowd, look up at the sky (where instead now flies an airplane trailing a huge banner for a local auto dealer).

But now, and for some time, you go to a game and there is constant entertainment. It's loud all the time. You're never alone with your own thoughts. It's pop entertainment. You really are a spectator far removed from the action because of the artifice surrounding the game: it's harder to hear the crowd; the amounts of money involved are insane; the demographic of the players is far removed from the demographic of the fan. It's basically show biz, but less predictable- they really are playing, though it's not very playful.

Instead, I see much more of the game when I watch college or high school ball. My favorite is to watch women's college softball- intense, fast, high level playing. Even at the high school level the game is fun to watch- the game itself is more open, more porous, closer to an ideal of baseball. There's no money involved and less racket. The pace of the game is more natural because there are fewer distractions to assure me I'm getting my money's worth. But the players still want to do well- they want to win, they want the attention, there's always the dream that some scout is out there.

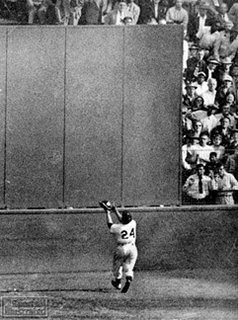

Somewhere in here is an idea about purity and purpose, about the potential to do something for itself, and for oneself, and for the team. Sometimes you watch a game and things flow- a double play, a player's swing, a beautiful duel between the pitcher and batter, or a moment of blind, intuitive movement of a body in space that turns out absolute, as in the picture of Willie Mays above making the famous over-the-shoulder catch.

Sometimes you see a painting and there are parts where you can see that the painter was in a groove, what Ron Gorchov called, "hallucinatory and difficult to explain." I like seeing that, and even more so, I like experiencing that. I am always looking for that, and it's possible to see it in all kinds of art, even in art that may not really be what one favors. That's the periphery I'm interested in. I am not opposed to, for example, the Leipzig painters, John Currin, Takashi Murakami, and so on... these are names that might go on some people's hit lists, we all have them. But I am not terribly interested in art that wants to act all big league, and tries to distract me with issues and entertainment.

Two

A few years ago I was in the optometrist's office waiting for an eye exam. There were a couple of large paintings on the walls, pastel colors, pictures of little blonde children out in nature, under trees. And they were kind of not so good, but they had enough going on where they were bumping up against being competent.

Rather than read Time or Sports Illustrated, I'd rather stare at paintings. And after a minute I noticed they were signed with the same last name as the optometrist. Turns out, his wife is the painter. And I kept looking.

I realized after a couple of more minutes of looking that these paintings were actually quite ambitious, at least compositionally, and the drawing was good enough not to interfere with the painting as a unit. They'd almost just about be passable at one of those wine and art festival things that the Chamber of Commerce likes to put on before Labor Day where women can wear their white dresses and men can wear their polo shirts and khakis and people can come out and see their friends and have a glass of chardonnay and feel cultured and civic minded. Not that there's anything wrong with that.

The wait at this particular office, to which I'd been a few times, can be a little long. That's part of why I don't go there anymore. This particular wait was close to half an hour. I just looked at those paintings, and gave them time, and got involved, and saw how the artist had to get involved, too. I saw her drawing problem, and got attuned to her palette, which although kind of predictable was also very consistent, and really got into her brushstrokes, and how she put on paint. And I could see that, despite the shortcomings of her subject, the predictable colors and the sentiment implied, that this artist was trying to seriously deal with these paintings. I realized that paintings which I wouldn't ordinarily give the time of day to still had a lot to offer if I'd just give them time. And I remember thinking, well, this is kind of like watching little league. The level of play isn't as high, but the game is still there, and I like the game.

Three

Go somewhere where there is a folk art tradition. You're a tourist, and you want to buy a sample. You're going to a central market where you're going to buy a piece of pottery. A painted plate. Let's say you're going to Mexico, to Puerto Vallarta, and you decide to buy a plate, something that you know kind of gets knocked out in production. And you know looking through stacks of these plastes that some of them are painted better than the others. There's a better touch, a nicer line, a little finesse at the end of the stroke, something a little more bold and confident, a feeling that the person who painted it really has a conceptual and physical grasp of the surface of this plate and how to decorate it. I like that.

Go somewhere where there is a folk art tradition. You're a tourist, and you want to buy a sample. You're going to a central market where you're going to buy a piece of pottery. A painted plate. Let's say you're going to Mexico, to Puerto Vallarta, and you decide to buy a plate, something that you know kind of gets knocked out in production. And you know looking through stacks of these plastes that some of them are painted better than the others. There's a better touch, a nicer line, a little finesse at the end of the stroke, something a little more bold and confident, a feeling that the person who painted it really has a conceptual and physical grasp of the surface of this plate and how to decorate it. I like that.Four

My grandmother was very supportive of my artistic inclinations. She bought me oil paints when I was eleven, the same day she took me to the Oakland Museum for the first time, during which three things happened.

A: The Oakland Museum has a typical Mel Ramos painting- a nude playmate type astride a brown bear. Certainly, for an eleven year old, I was curious about the nude. And my grandmother didn't want me looking at it. But I knew it was a painting, and that's what really interested me. I don't think she understood the difference, but I did, and I saw, besides his basically puerile subject, that there was some paint going on there. That was a moment.

A: The Oakland Museum has a typical Mel Ramos painting- a nude playmate type astride a brown bear. Certainly, for an eleven year old, I was curious about the nude. And my grandmother didn't want me looking at it. But I knew it was a painting, and that's what really interested me. I don't think she understood the difference, but I did, and I saw, besides his basically puerile subject, that there was some paint going on there. That was a moment.B: I saw real abstract paintings for the first time. We're talking around 1968, so what I would've seen at this particular museum would've been SF Bay Area AbEx (Still, Corbett, Francis, Hassel Smith, maybe Lorser Feitelson) extending back through to California Surrealism (Helen Lundeberg, blanking on other names) and further back to a kind of late Cubism (Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Lucien Labaudt). And throw in a minimalist kind of thing, like John McLaughlin, a personal favorite. I dug it.

C: After the visit my grandmother took me to a paint store with an art section (RIP Standards Brands paint store) and bought me a set of oils and some canvas paper, and I made my first abstract painting at her house. She would've liked a nice still life, some flowers, but she didn't say so. I liked the paint; it was difficult, but it was a start.

When I paint, I often think back on A, B, and C, and all the other similar experiences and odds and ends in my periphery that have been about looking and paint.

I will write more about the question of how far back do I look, and what has been important to me.

No comments:

Post a Comment