Chris, you ask how far back I look, what I look at, and what I get out of it. The short answer to your first question is that once I leave the 20th and 21st centuries, I look as far back as there's art.

Chris, you ask how far back I look, what I look at, and what I get out of it. The short answer to your first question is that once I leave the 20th and 21st centuries, I look as far back as there's art.

Color aside, I guess I'm drawn to these two paintings in part because of their degree of abstraction--though I realize I'm looking at them with 21st century eyes. The di Paolo painting, in particular, rocks me to the core every time I visit it at the Met (at the spectacular Lehman Wing). Here, before Copernicus (b. 1473), before Columbus sailed off the edge of the earth and returned to tell about it, di Paolo conceived of a universe in abstract terms. I'm not a historian of art or anything else, but I think some planets had been identified by the mid fifteenth century, and that Dante had already put forth his idea of the Celestial Wheel, but here we see di Paolo's visual conception of the universe as one compact Big Bang.

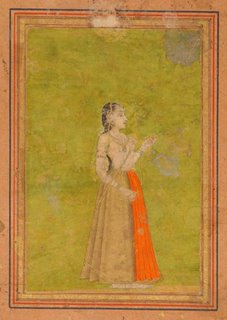

I also love miniature painting from Mughal India and elsewhere in which that tradition was practiced. (I have visited the Morgan Library many times to see illuminated manuscripts, and I'm remembering a show at the Lorenzo di Medici library in Florence in which the manuscripts were encrusted with gems. Gilding the lily for sure.) Here, too, it's the color. But also the scale. Well, the relation of the colors within the scale, and in relation to the scale. These are things I think about in my own painting, too.

I also love miniature painting from Mughal India and elsewhere in which that tradition was practiced. (I have visited the Morgan Library many times to see illuminated manuscripts, and I'm remembering a show at the Lorenzo di Medici library in Florence in which the manuscripts were encrusted with gems. Gilding the lily for sure.) Here, too, it's the color. But also the scale. Well, the relation of the colors within the scale, and in relation to the scale. These are things I think about in my own painting, too.

Portrait of a Woman, Mughal India; gouache on paper, Jahangir period, app 1605; 4" high

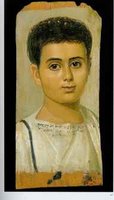

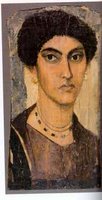

Farther back, I like to see the Fayum portraits. The Met has five beauties, of which Eutyches, below left, is one. The portraits, which are about life size, are the earliest surviving examples of encaustic painting. Even before I started working in wax, I used to stop by the case in which the portraits are housed. These are portraits of real people, people who looked the artist in the eye as they sat, knowing they would live again in the great Egyptian afterlife and in the meantime remain young forever in their likeness of wax on panel. The Fayums, named after a Nile Delta oasis near where many of the portraits were untombed, were painted in a roughly three-hundred-year period around the cusp between BC and AD, the product of Greco-Roman Egypt. After a sitter's death, the portrait was placed in the wrapped mummy above where the actual face would be, to look out into the world of the great beyond. Talk about multiculture: Greek colonists living in Roman-controlled Egypt, creating portraits to be placed on mummy casings for traditional Egyptian burial rites. I believe the Fayums are the earliest extant paintings made on a portable ground.

From left: Eutyches, at the Metropolitan museum of Art, New York; Isidora at the Getty, Los Angeles; Woman at the National Gallery, London

You realize I'm just scratching the surface here. I might also add Artemisia, not only as a strong painter but as a model of strength against adversity. Giotto, who with the Middle Ages at his back, opened the picture to more a dimensional space.

Changing centuries, I also like stuff we would call "ethnic" --Amish and African-American quilts (a la Gee's Bend); Navajo and Hopi textiles; the sculptures of Kuan Yin and mandalas from throughout the East, the Islamic Wing at the Met with its integration of textiles, pottery, caligraphy and architecture.

Clockwise from left: Vajrayana mandala, Mongolia, 19th century; Amish quilt, Lancaster, Pa., 1930's; Zulu telephone wire basket, contemporary; Lola Petway, Bars

, 2004, Gee's BendCan we make a conceptual leap from di Paolo's universe to the one depicted by the mandala? And a visual one to the mandalas of the basket and Amish quilt? Can we  connect the quilts to geometric abstraction from the Sixties to now?

connect the quilts to geometric abstraction from the Sixties to now?

I feel like those actors at the Academy Awards who have to name everyone who ever made a difference in their lives. My agent, my manager. I love you all.

I feel like those actors at the Academy Awards who have to name everyone who ever made a difference in their lives. My agent, my manager. I love you all.

So, what do I get out of all this? As an artist, I find it humbling that what I do, what artists in general do, is pretty much exactly what artists have done throughout history. We daub pigment onto a prepared surface, we handle clay, we stitch cloth, hammer metal, sculpt wood. I know there are 20th and 21st century mediums that don't have the same lineage, but the urge to express, to create, to make manifest is the same urge that the cave painters must have had. So, I guess it's connecting culturally to a world that is not just of this place and to a time that is not just of the present.

Shall we pursue this thread for a bit? Tell me more about what you like to look at.

No comments:

Post a Comment