JOANNE MATTERA

"Heat of the Moment: New Paintings in Encaustic"

Arden Gallery, Boston, September 5~30

Reception: Friday, September 8, 5-7 pm

Gallery Talk: Saturday, September 9, 1pm

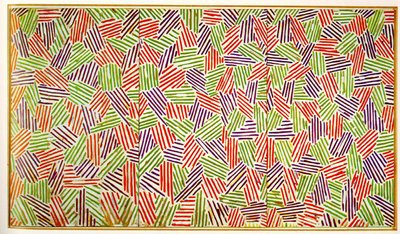

JM: Quadrate 2, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48 inches, 2006

In my blog, I'll shortly be posting a piece on painting in acrylic As you know, my primary medium is encaustic. I'll update this post soon with a link.

But enough about moi. Where do you think your own work will go with Bojagi? A series? And we're about to start a new month. What direction will your HTML drawings take?

Another reader of this conversation, a painter, (I'm not sure if people want to be outed as a reader without their permission), wrote to me about Imi Knoebel. This painter, first initial "K", is a different reader than the person, a non-painter, who wrote to me about Schur and Wilson. So we know we've got at least two readers.

Another reader of this conversation, a painter, (I'm not sure if people want to be outed as a reader without their permission), wrote to me about Imi Knoebel. This painter, first initial "K", is a different reader than the person, a non-painter, who wrote to me about Schur and Wilson. So we know we've got at least two readers. "The lighting wasn't so great I thought in the gallery- kind of harsh, showed imperfections across some of the surfaces and at the edges that, given the way the paintings are made, seemed out of place. No way could I have known from pix on gallery web site that he was contrasting thin vs. built-up areas, and matte vs. shinier surfaces. That didn't work so well for me.

And I was trying to understand the purpose for planes to wrap around the sides of the canvas, as if the planes on the front that continued around to the side were portions of a 3-D block embedded in the canvas- do you know what I mean, that he was making the canvas an object but also some of the planes on the front of the canvas began to feel like 3-D rectangles because they wrapped around the edges to the side? That and the consistently close valued, muted colors just didn't come alive for me."

Ahhhhhh. The hint of geo, and the biological/organic feel. That was my sort of somewhat kind of aimless intention. I think. And they're painterly. They're kind of rough. They look very fast, but they were made very slowly. Those things hung on the wall, and over several weeks I'd walked past them, take a pass at them, let them hang some more. They took a long time. I did not set out to make three paintings based on the same drawing. I've never done that before. Ever. You saw it here first- history! I tend to try to make every painting be different.

Ahhhhhh. The hint of geo, and the biological/organic feel. That was my sort of somewhat kind of aimless intention. I think. And they're painterly. They're kind of rough. They look very fast, but they were made very slowly. Those things hung on the wall, and over several weeks I'd walked past them, take a pass at them, let them hang some more. They took a long time. I did not set out to make three paintings based on the same drawing. I've never done that before. Ever. You saw it here first- history! I tend to try to make every painting be different.

Bojagi (Pojagi), or wrapping cloths, are Korean textiles pieced together from small scraps of cloth. Bojagi have very old origins, but those still in existence date from the Choson dynasty (1392 – 1910). They are used for wrapping, carrying and storing objects, and as table coverings, altar cloths and special-occasion decorations. Bojagi are usually square and come in a range of sizes. Fabrics used in bojagi include silk, cotton, hemp and ramie. Ramie is a fiber made from the stalks of a woody shrub indigenous and unique to Korea. It can be woven into a very thin, even-textured and strong fabric that is extraordinarily long-lasting. There are many different types of bojagi including lined or unlined, embroidered, painted and gold-leafed (URL).

I have a lot of stuff in progress. I'm really just painting kind of whatever I want- I'm feeling very loose, and I'm very open to all kinds of imagery. What I'm doing is rolling right out of what I've been doing since around fall 2004, and getting a whole lot more comfortable with oil and all of the different ways it can be handled. I like that my approach, and the variety of the work, still feels to me part of a single overall approach, and I like that I don't feel locked into a certain way of painting. I like being able to work in bursts and smaller series, to shift gears, to have some works that belong together but are separate from another group of work. I'm liking the domestic, intimate, personal feel of what I'm doing- these are smaller issue paintings, intimate, but also painting in a way that is critical of painting and its history and possiblities, all while staying within the tradition- oil, on canvas, over stretchers, on the wall. Nothing radical? I feel that this kind of low tech approach, in the face of so many things that are depersonalizing, in a time of the absence of the original, next to so much art that is not about the unique handmade object, that this little domestic approach has the possilibity of being very radical. I'm thinking of this idea of a domestic kind of art as acoustic, like playing acoustic guitar rather than big plugged-in electric, but acoustic with a bigger idea in mind- playing acoustic guitar and recording it with iTunes to be used in a larger context than one's porch or backyard. Just thinking, just wondering what this is and where it goes. Also, I think, actually, that this approach is realistic. I have a day job. I have a small place to work. I'm very busy. I don't have hours on end in the studio. I don't think my ambition is to make ten foot paintings. I'm trying to be realistic about how painting is part of my life. I'm in it for something other....

few years ago turned her attention to compositions with blocks of color, as if she’d distilled her world and organized it into neat little swatches. Wilson’s oil paintings in this show are small—8 x10 to 20 x 16 inches—with squares or rectangles organized into grids in which the uniformity of shape is broken by occasional feathering as one color leaches tentatively into another, or a skew of size or out-of-step placement. Green predominates. Or is it red? Or umber? There’s a lot of give and take there, but the work remains lyrical to my eyes.

few years ago turned her attention to compositions with blocks of color, as if she’d distilled her world and organized it into neat little swatches. Wilson’s oil paintings in this show are small—8 x10 to 20 x 16 inches—with squares or rectangles organized into grids in which the uniformity of shape is broken by occasional feathering as one color leaches tentatively into another, or a skew of size or out-of-step placement. Green predominates. Or is it red? Or umber? There’s a lot of give and take there, but the work remains lyrical to my eyes.  Down the street at the Ernden Gallery another artist whose work I like is represented: Carlos Estrada-Vega. He’s also working with blocks, and his scale is also modest. But whereas Wilson’s paintings are flat and relatively uninflected, Estrada-Vega’s are physically dimensional. Each painting is a relief composed of hundreds of individual canvas-covered blocks that he colors with wax paint (something he calls oleopasto) that are adhered onto a metal plate by means of tiny magnets embedded in each block. The work is called painting, but it’s also relief sculpture as the individual units vary by height. There’s so much going on—the topography, the colors in quiet or spirited conversation, and textures modulating the exchange.

Down the street at the Ernden Gallery another artist whose work I like is represented: Carlos Estrada-Vega. He’s also working with blocks, and his scale is also modest. But whereas Wilson’s paintings are flat and relatively uninflected, Estrada-Vega’s are physically dimensional. Each painting is a relief composed of hundreds of individual canvas-covered blocks that he colors with wax paint (something he calls oleopasto) that are adhered onto a metal plate by means of tiny magnets embedded in each block. The work is called painting, but it’s also relief sculpture as the individual units vary by height. There’s so much going on—the topography, the colors in quiet or spirited conversation, and textures modulating the exchange.  Inman works with the grid, but she defines each square with a dot. Specifically, she paints dots that have been arranged in logarithmically patterned formats. Working on a large-scale printout that she adheres to her painting surface, Inman builds up her surface dot by dot, color over color, often returning to sand away parts of those dots to reveal the edges of the color beneath. At the same time that the work feels twenty-first-century current, the sanding gives it a distinct archeological sensibility. Reese’s new series is called Maps, and the work suggests both the means to a destination and the destination itself. You can see more on her website. She’s also represented by Gallery Naga in Boston.

Inman works with the grid, but she defines each square with a dot. Specifically, she paints dots that have been arranged in logarithmically patterned formats. Working on a large-scale printout that she adheres to her painting surface, Inman builds up her surface dot by dot, color over color, often returning to sand away parts of those dots to reveal the edges of the color beneath. At the same time that the work feels twenty-first-century current, the sanding gives it a distinct archeological sensibility. Reese’s new series is called Maps, and the work suggests both the means to a destination and the destination itself. You can see more on her website. She’s also represented by Gallery Naga in Boston.  Since I’ve been working blocks and bands for some years, I’m always interested to see how these and other other artists organize their geometry and how their palette integrates with the geometry. Indeed, "blocks of color" is a simple description, but the expression of the concept is infinitely varied and vast. And of course you are composing your HTML drawings with rows and blocks of color. (I love that the cut-and-paste mechanics of their making leads to to also think of them as collage.)

Since I’ve been working blocks and bands for some years, I’m always interested to see how these and other other artists organize their geometry and how their palette integrates with the geometry. Indeed, "blocks of color" is a simple description, but the expression of the concept is infinitely varied and vast. And of course you are composing your HTML drawings with rows and blocks of color. (I love that the cut-and-paste mechanics of their making leads to to also think of them as collage.)Below: Mensie Lee Petway, Strips, pieced quilt, 2003

Left: Peruvian tapestry fragment

Right: Young monks in a Bhutan monastery facing a painted or tiled wall. The block pattern is very much like the the 1930s Amish quilt from Lancaster County, Pa., below

Below: Mondrian, Contexture, oil on canvas, 1930s; above: another 1930s Amish quilt. Do I need to comment on all the visual connections?

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

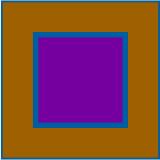

When I Met You (Pacific), 20060720, HTML, 300 x 400 pixels